Midweek Writer-Rummage: The World of 'Moon Goddess'

I don’t think I made a conscious decision as to what kind of world to use in the ‘Moon Goddess’ story. When I started writing, it felt right to set it in a medieval-type world, similar to early medieval England.

Using that as my base made it easy in that I didn’t have to think about the laws of nature and physics; they would be the same as in our world. As for the inhabitants, there wouldn’t be any other races, other than humans. Most of the other factors that are taken into account when it comes to world-building are basically the same as that of medieval England, including the physical features of the land, social organisation and daily life.

A lot of my research was to do with what life was like then. I dipped into a few books and online articles but the one book I found invaluable was ‘The Year 1000: What life was like at the turn of the first millennium’ by Robert Lacey and Danny Danziger. They used the Julius Work Calendar as their base to discuss how ordinary people lived through the year with the chapters divided into the months of the year.

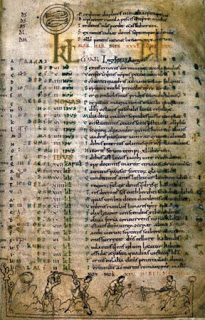

This Calendar is thought to have been written around the year 1020. Its layout is 12 months written on 12 pages; each sheet headed with the name of the month and the sign of the zodiac, which I, personally, found interesting. The days of the month are listed down the page and, right at the bottom, are endearing little illustrations showing the task of the month – for example, January depicts ploughing; May shows shepherds with their flock; and August, harvesting.

I learned so many interesting things from this book, which went a long way in helping me present a believable world. And they weren’t necessarily ‘big’ things; I’m talking relatively small things:

- Underwear was made of coarse hand-woven wool which made it scratchy; only the wealthy could afford linen garments.

- Clothes weren’t limited to brown. Natural vegetable colourings produced strong colours like reds, greens and yellows.

- Buttons had not been invented so clothes were fastened with clasps and thongs.

- Cutlery hadn’t been invented; the eating fork was only invented in the 17th century. When you went to a feast, you had to take your own knife.

- There was no sugar so honey was used to add sweetness. The absence of sugar meant there was no dental or jaw decay.

- Bread back then was more important than meat, milk or vegetables; it was round, coarse and flat, with the texture of pitta bread.

- There were copious varieties of fruit including apple, pear, plum, fig, quince, peach, and mulberry; also chestnuts, almonds and hazelnuts. Vegetables included onions, leeks, celery, radish, carrots, garlic, shallots, parsnip, cabbage, lettuce, parsley, dill and coriander. But there was no spinach, broccoli, cauliflower, runner beans, Brussel sprouts, potatoes, and tomatoes. Neither was there tea, coffee or chocolate.

Village society usually consisted of the lord of the manor/castle; his officers (reeves and bailiffs); the priests; and a peasant population of sokemen (or freemen who paid cash or goods for the land they rented), villeins (bound to the land and could not leave to farm elsewhere) and slaves.

Depending on factors such as local weather conditions and drinking habits, about half the land would be sown in barley, which was needed for making ale. A third would be planted in wheat; the remainder in peas and oats. Farmers also kept:

- one or more horses and oxen for pulling the plough and other heavy work

- a couple of milk cows for milk which was turned into cheese

- a few pigs, which were fattened for major feasts

- several dozen sheep, which supplied wool

- beehives

- chickens and geese, which supplied meat and eggs to enhance a diet of peas and porridge

The houses of the peasants were very basic with, possibly, only one small window to minimise drafts; only the rich could afford glass in their windows. This meant the inside was usually dark. The floor was flattened earth, and there was usually either 1 or 2 rooms. The furniture was minimal, consisting of a table and stools, maybe a chair. With the cooking fire constantly lit, the accumulated smoke must have been unbearable.

One of the things that surprised me was discovering that people in those times were tall, similar to people of today; they were strong and healthy. Many lived in the countryside on “ a simple, wholesome diet that grew sturdy limbs, and very healthy teeth.” They were practical, skilful with their hands. I guess if I’d stopped to think about it, I’d have realised just how mentally adept they must have been; their knowledge didn’t come from books as very few could read. Everything they learned they did by observing and imitating, “usually by standing alongside an adult who was almost certainly their mother or father, and by memorising everything they needed to survive and enrich their lives.” And they remembered it all!

Life for the average medieval person was very routine, with most of the time spent working the land. It’s no surprise that social activities were very important, as was music. Weddings were traditional folk ceremonies, a ritual of toasts, vows and speeches enjoyed with the rest of the village.

Interestingly, divorce was allowed. There were no ethical hang-ups about it, so long as the practicalities were taken care of, basically the apportioning of property and the care of the children. One Anglo-Saxon law code makes clear that “ a woman could walk out of her marriage on her own initiative if she cared to, and that if she took the children and cared for them, then she was also entitled to half the property.”

The laws of the time were tough and very matter-of-fact. With gallows positioned outside every town and at crossroads, hanging was the most effective deterrent in an age with no law-keeping force or prisons.

The story doesn’t feature anyone writing but this snippet of information is so fascinating, I think it requires sharing. And it’s a nicer way to end the post. This is how ink was made:

“It was an oak tree that provided the ink, from a boil-like pimple growing out of its bark. A wasp had gnawed into the wood to lay its eggs there, and, in self-defence, the tree had formed a gall around the intrusion, circular and hard-skinned like a crab apple, full of clear acid. ‘Encaustrum’ was what they called ink in the year 1000, from the Latin causter, ‘to bite’, because the fluid from the galls on an oak tree literally bit into the parchment, which was flayed from the skin of lamb or calf or kid. Ink was treacly liquid in those days. You crushed the oak galls in rainwater or vinegar, thickened it with gum arabic, then added iron salts to colour the acid.”

Before I go, just to let you know I won’t be posting on Friday but will continue, as usual, on Sunday.