The Sunday Section: Snippets of ... Medieval Life

This came about from research I did for one of my stories, which is set in a land similar to medieval England. These facts are mainly about 11th century life …

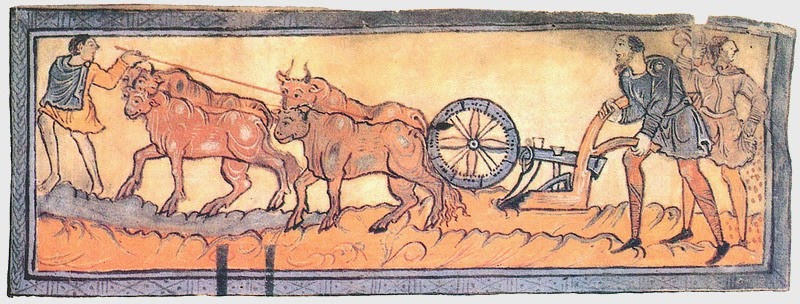

Ploughing with oxen

People back then were tall, similar to people today. Because there was no sugar, there was barely any dental decay. And no sugar meant that honey was the main source of sweetness. Bees also produced propolis, the reddish resin used by worker bees as a building material; because of its healing properties, it was used for the treatment of wounds.

Clothes were colourful, with natural vegetable colourings producing strong hues –

- dark brown was obtained from bracken

- yellow from chamomile flowers, apple, ash or birch

- green from young heather shoots or boiled nettle leaves

- carmine from the inner bark of the birch tree

- purple from dandelion or elderberries

- grey from silver birch bark

- navy blue from blackberry juice

- black from oak or blackberry juice boiled with ivy leaves.

Underwear was scratchy, made of coarse wool; only the wealthy could afford linen.

No stone buildings and no iron bars meant there were no prisons. So penalties for breaking the law was usually either execution, paying of fines, or slavery. As impoverished offenders had no money to pay fines, the only thing they could forfeit was their labour. Under the ‘wergild’ system, every man and woman had their price; the cost of a human life was 125lbs of silver. Because a price was attached, it was possible for a rich, murderous nobleman to avoid the death penalty by paying for the life he had taken; no such luck for the poor.

For many ordinary people, life was a constant struggle. In times of famine or when they could not provide for their families anymore, the starving man would surrender himself into bondage. If there truly was no other choice, a father could sell his son aged under seven as a slave; even infanticide wasn’t seen as a crime.

A ‘villein’ was a person who was a serf with respect to his lord, but who had the rights of a free man with respect to others. His house was made of wattle – thin branches of wood woven together, and covered with daub – a mixture of clay, oxhair and dung. Despite having their own crops to harvest, villeins were expected to harvest their lord’s crop first – working from dawn, (about 6am) to dusk (about 10pm), it was back-breaking work.

Shepherds tending sheep

Meat – the principal ingredient for a feast. Though beef was considered the best, the most highly prized was venison. Poultry was considered a luxury food. Other fowl included ducks, geese, pigeons, and other game birds. Mutton was seen as a food for slaves.

The medieval pig, which had more of a boar-like appearance, was free-range, lean and rangy, its meat containing 3-times as much protein as fat. It was the most commonly kept animal as every bit of it could be used – sides of bacon were hung in the rafters and smoked; its stomach lining provided tripe; intestines provided skin for sausages; its blood was the main ingredient for black pudding.

As cutlery hadn’t yet been invented, people took their own knives when they went to a feast. It wasn’t until the 17th century that the eating fork was invented.

Smith heating iron in fire

Fish caught in rivers included eels, minnows, trout, pike, burbot and lampreys.

Fish caught from the sea included salmon, sturgeon, oysters, crabs, herrings, flounders, porpoises, mussels, cockles, plaice, winkles, and lobsters.

Mead – a very sweet, potent alcoholic drink, brewed from the crushed refuse of honeycombs.

‘Beor’ – not that strong; as it did not keep well, it was consumed without delay.

Wine was not a very common drink, and was less alcoholic than mead. It was consumed soon after harvest and wasn’t intended to last very long.

The most common drink was ale; being boiled and brewed, it was safer to drink than water.

In July, ironically on the cusp of the August harvest, people were most likely to find themselves starving. The rich had the contents of their barns to see them through, and the money to pay for gradually soaring prices of food. But the poor were forced to grind up coarse wheat bran, and old peas and beans, even bark, to make a sort of bread. They would scavenge the woods for beechnuts and food normally left for pigs; and hunt the hedgerows for herbs, nettles, and roots in a bid to relieve the pains of starvation.

August 1st was Lammas Day, one of the oldest English country festivals, originally called ‘hlaf-maesse’, or loaf-mass when the first loaf was made from the new harvest.

Harvest

Observing animals helped predict the weather – horses get restless and shake their heads just before rain; sheep lying quietly points to the weather being fine, but if they’re up and grazing early, or huddling together by bushes, then it will rain; restless cattle running around the pasture means there is a thunderstorm brewing.

Hunting was something every free-born Anglo-Saxon had the right to do, until the Normans introduced hunting restrictions.

Herbal remedies included:

- wormwood, to purge the digestive system of worms

- lungwort, to treat chest illnesses

- lemon balm, for anything from colds to serious conditions

- feverfew, for headaches and labour pains

- marjoram, for bruises

For the Romans, living in a city meant you were civilised; barbarians were considered ‘uncivilised’ because they did not live in cities, preferring villages, which was what they were used to. Even after the Romans left, the people still preferred villages. It was only in the reign of King Alfred, when the threat of Vikings became real, were networks of defended settlements built, known as ‘ burhs’ – the root word for the modern borough.

Glass – beechwood ash fired in a charcoal furnace with washed sand – was a precious, expensive commodity, most likely imported.

Music was a fundamental part of everyday life, even played during mealtimes, as it was believed that music helped the digestion of food. The types of instruments used included recorders, horns, trumpets, whistles, bells and drums. During weddings, a mock serenade, called ‘chivaree’, was played by banging pans and kettles in a mock serenade to the newlyweds. On Mayday, the music played for the dancers was deliberately high-pitched; this was to awaken hibernating spirits and warn them that spring had arrived.

Musicians

The word ‘sheriff’ comes from ‘shire reeve’, basically the king’s representative in the shire.

If you were a mile away from a battle, you wouldn’t hear anything because of the absence of gunfire or explosions. The battle was basically a series of muffled confrontations augmented by the clang of sword on sword, and by war cries.

Norman Conquest

Men were called ‘waepnedmenn’, ‘weaponed-persons’; women were ‘ wifmenn’, ‘wife-persons’, with ‘wif’ being derived from the word for weaving.

The law did not require that a bride had to be a virgin. Marriage law was basically about the allocation of property, and the male heads of households negotiated the ‘ morgengifu’, or the ‘morning gift’ to be paid by the husband after a satisfactory wedding night. Because the gift (could be money and/or land) was paid to the wife, it was in her best interests to maintain her virginity.

It’s easy to assume that because the vast majority of medieval people didn’t know how to read, they were probably not that bright. But they stored all their knowledge in their heads, having learned everything by observing and imitating, as children, the adults around them who passed on their skills; they basically memorised everything they needed to know to survive.