Magical Objects Series - Part Seven: Japanese Mythology

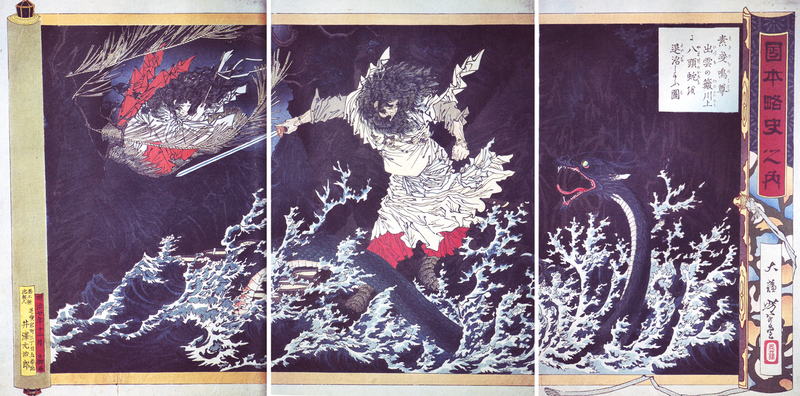

Susanoo slays Yamata-no-Orochi, woodblock by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (WCommons)

Japanese mythology is a combination of the two primary religions of Japan, Shinto and Buddhism, and folk religion associated with the forces of nature.

Shinto involves the worship of kami or deities and revered spirits, a huge number of which are part of the Shinto pantheon.

The folklore of Japan was influenced by literature from India and China, albeit changed and adapted so the Japanese would find them more appealing.

For example, the monkey stories of Japanese folklore bear the characteristics of the Sanskrit epic, ‘Ramayana’, and the Chinese ‘The Journey to the West’.

I’ll start the list with the Three Sacred Treasures, the Imperial Regalia of Japan – the sword, Kusanagi-no-tsurugi, which represents valour; the mirror, Yata no Kagami, which represents wisdom; and the jewel Yasakani no Magatama, representing benevolence.

All 3 are kept from public view to symbolise their authority.

‘Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi’.

Susanoo watching Yamata-no-Orochi swimming (WCommons)

This legendary Japanese sword was originally called Ame-no-Murakumo-no-Tsurugi, the ‘Heavenly Sword of Gathering Clouds’ before its name was changed to Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi, ‘Grass-Cutting Sword’.

Legend ties this sword with Susanoo, the younger brother of Amaterasu, goddess of the sun.

He is said to possess contradictory characteristics, sometimes portrayed as a wild and impetuous god, at other times as a heroic figure.

Susanoo is banished from heaven after killing one of Amaterasu’s attendants and destroying her rice fields.

Descending to earth, he comes across two grieving ‘Earthly Deities’ who tell him their family is being terrorised by the Yamata no Orochi, the ‘Eight-Branched Serpent’, who has already consumed 7 of their 8 daughters and will soon come for the last one, Kushi-inada-hime.

Susanoo promises to help the family and transforms Kushi-inada-hime into a comb for safekeeping.

The Yamata no Orochi is described as having ‘an eight-forked head and an eight-forked tail; its eyes were red, like the winter-cherry; and on its back firs and cypresses were growing. As it crawled it extended over a space of eight hills and eight valleys.’ (‘Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to AD 697 (2 vols.)’, translated by William George Aston.)

After investigating the creature, Susanoo comes up with a plan that involves a fence with 8 gates, a platform tied to each gate, and on each platform, a vat of saké.

When the eight-headed serpent comes, each head drinks the sake from all 8 vats, and intoxicated, all the heads fell asleep.

Susanoo swiftly draws his sword, the Worochi no Ara-masa, a ‘Sword of Ten Hand-Breadths’, and cuts off the 8 heads and then the tails.

When he cuts the 4th tail, his sword breaks.

Inside the tail, he finds a great sword, the Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi.

Returning to heaven, Susanoo offers the sword to his sister, Amaterasu, as a gift of reconciliation.

‘Yata no Kagami’.

The mirror, representing wisdom, was offered to Amaterasu, and is considered the most precious of the Three Sacred Treasures.

In ancient Japan, mirrors represented truth because they reflected what was shown.

‘Yasakani no Magatama’.

Amaterasu holding a magatama necklace in her left hand, and a sword in her right (WCommons)

This jewelled necklace was also offered to Amaterasu.

Magatama, curved beads that appeared in prehistoric Japan, were also described as jewels.

Originally made of stone and earthen materials, magatama was used as decorative jewellery.

By the 6th century, they were made almost exclusively of jade and used primarily as ceremonial and religious objects.

‘Ama-no-Nuboko’ or ‘Heavenly Jewelled Spear’.

Izanami (L) & Izanagi (R) raising the land with the spear Ama-no-Nuboko, painting by Eitaku Kobayashi (WCommons)

A pole weapon known as a ‘naginata’, this spear was used by the Shinto creator deities, Izanagi, and his sister-wife, Izanami, the last of the 7 generations of primordial deities that manifested after the formation of heaven and earth.

A naginata forged by Osafune Katsumitsu, Muromachi period 1503 at Tokyo National Museum, photo by SLIMHHANYA (WCommons)

They are believed to be the creators of the Japanese archipelago, and the ancestors of many deities, including Amaterasu, Susanoo, and the moon deity, Tsukuyomi.

They went to the bridge between heaven and earth and used Ama-no-Nuboko to churn the sea.

When drops of salty water fell from the tip of the naginata, they formed the first island, and Izanagi and Izanami descended from the bridge and made their home on the island.

‘Uchide no kozuchi’.

Daikokuten (L) and Ebisu - Museum of Fine Arts Boston (WCommons)

Literally a magic hammer, this wooden hammer can ‘tap out’ anything that’s wished for.

It is a standard item held by the deity of fortune and wealth, Daikokuten, who originated from Mahākāla, the Buddhist version of the Hindu deity, Shiva, merged with the Shinto god, Ōkuninushi.

‘Kongō’.

A trident-shaped staff which originally belonged to the mountain god, Kōya-no-Myōjin, it could emit a bright light in the darkness, and granted wisdom and insight.

‘Takarabune’ or Treasure Ship.

Takarabune at Victoria & Albert Museum (WCommons)

A mythical ship that was piloted through the heavens by the Seven Lucky Gods during the first 3 days of the New Year.

Seven Lucky Gods - (clockwise from left) Ebisu, Hotei, Fukurokuju, Jurōjin (centre), Bishamonten (with spear), Benzaiten, and Daikokuten.

Collaborative painting by Katsushika, Kunisada, Toyokuni, Kiyonaga, Hokusai - early 19th century (WCommons)

The Seven Lucky Gods are:

Ebisu, from the same period as Izanagi and Izanami, his origins are purely Japanese. He is the god of prosperity and wealth in business, abundance in crops and food, and the patron of fishermen.

Daikokuten, already mentioned, the god of fortune and wealth.

Bishamonten whose origins can be traced back to Hinduism and the god Kubera, he is the god of fortune in war and battles and is the patron of fighters.

Benzaiten is the only female deity in this group and comes from the Hindu goddess Saraswati, with the attributes of financial fortune, talent, beauty, and music.

Jurōjin, considered the incarnation of the southern pole star, is the god of the elderly and of longevity.

Hotei is the god of fortune, guardian of children, patron of diviners and barmen, and the god of popularity.

Fukurokuju has his origins in China, and is the god of wisdom, luck, longevity, wealth, and happiness.

‘Kappa’s plate or ‘Kappa’s sara’.

Kappa (WCommons)

A kappa is a reptilian-like kami, which has similarities to yōkai, which are a class of supernatural entities and spirits.

Kappa are usually depicted as green, humanoid beings with webbed hands and feet, and turtle-like carapaces on their backs with a depression on its head, called its dish, or sara, that retains water.

When a kappa believes it’s not being respected as a god, it can become harmful.

The actions of kappa range from fairly harmless misdeeds to downright wicked, including drowning people and animals, kidnapping children, and eating human flesh.

The easiest way to defeat a kappa is to make it spill the water from the sara on its head as the water is the source of its power.

‘Kogitsune-maru’ or ‘Little Fox’.

Blacksmith Munechika helped by a fox spirit (surrounded by little foxes), forging the blade Ko-Gitsune Maru (“Little Fox”) (WCommons)

This sword features in the ‘Nō’ play ‘Kokaji’.

The emperor dreamt of a sword specially forged for him, so sent his envoy to the swordsmith, Munechika, to order him to forge a sword for the emperor.

Munechika had no assistant, but didn’t want to offend the emperor by refusing, so went to an Inari shrine to pray for help.

Inari are the kami of foxes, amongst other things, and are one of the principal kami of Shinto; in earlier Japan, they were also the patron of swordsmiths and merchants.

As Munechika prayed, a young boy appeared and told him to clean and purify his forge and the boy would come and work as his assistant.

In the morning, Munechika donned white clothing similar to what Shinto priests wore, and cleaned and purified his forge, and the boy appeared.

The swordsmith realised he was receiving divine help and humbled himself before the boy.

Then the swordsmith and the boy began to forge a sword.

But the boy’s abilities far surpassed that of a human, knowing exactly what to do when without requiring any instructions from Munechika.

The blade that was forged exceeded Munechika’s expectations, and he knew the emperor would be pleased.

Munechika signed the front of the blade with his name, Kokaji-Munechika, and to show his gratitude for the assistance he had received from the Inari, he added Kogitsune, which means ‘little fox’, to the back of the blade.

‘Tonbokiri’ or ‘Dragonfly Slaying Spear’.

Replica of the Tonbogiri in Tokyo National Museum - photo by Ihimutefu (WCommons)

One of the 3 legendary Japanese spears created by the famed swordsmith, Masazane Fujiwara.

Tonbokiri was said to have been wielded by Honda Tadakatsu, the legendary samurai, general, and daimyō (feudal lord) who served Tokugawa Ieyasu, the founder and first shōgun of the Tokugawa Shogunate, which ruled from 1603 until the Meiji Restoration in 1868.

Honda Tadakatsu (WCommons)

The spear’s name comes from the myth that a tonbo, or ‘dragonfly’, had landed on the blade and was instantly cut in two; kiri means ‘cutting’ in Japanese, hence ‘Dragonfly Slaying Spear’.