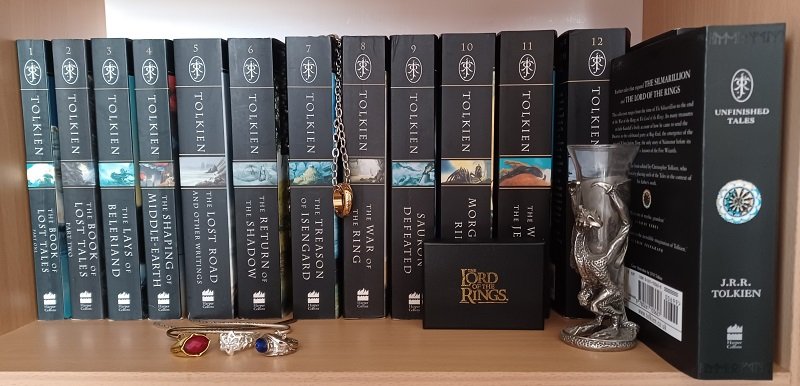

Book Review - 'The History of Middle-earth' Volumes 1-12 by J.R.R. Tolkien, Edited by Christopher Tolkien

‘The History of Middle-earth’ by JRR Tolkien and Christopher Tolkien

‘The History of Middle-earth’ was compiled by Christopher Tolkien after his father’s death.

This immense task lasted many years of Christopher’s life, and I can’t even begin to imagine the patience and dedication required for such an undertaking.

He painstakingly went through all his father’s papers, including scribbled notes on scraps of paper.

Following in his father’s footsteps as it were, Christopher then edited all the information he had collected with as much detail as JRR Tolkien had invested in documenting his legendarium.

He literally included every little thing, sometimes devoting whole chapters to just a fragment he thought might be of interest to the reader.

I applaud his perseverance in what was obviously not an easy task, as Christopher described his father’s writing thus in ‘The War of the Ring’:

“… excruciatingly difficult handwriting…”; “… my father’s most impossible handwriting, effectively indecipherable…”; “… pencilled text… fearsomely scrawled…”

Much of the content in these 12 volumes comprises earlier versions of Tolkien’s published works, and new material.

Having said that, the ‘History’ is not a chronicle of every single event that occurred in Middle-earth, but more an insight into the ‘works-in-progress’ of what would become ‘The Silmarillion’ and ‘The Lord of the Rings’.

So, bear in mind that these volumes do not constitute a story, with a beginning, middle and end, which means ‘The History of Middle-earth’ is not the best introduction to Tolkien.

Each volume also has Christopher’s own editorial insights and comments, which I found helpful.

Some might see that as adding a confusing layer, but there are spaces separating his comments from his father’s words; also, his comments are in a smaller font size.

He’s arranged the 12 volumes to, basically, show how his father created his Middle-earth legendarium, which lasted near enough his entire life and it’s laid out, more or less, chronologically alongside Tolkien’s own life, starting around 1915.

If ‘The Lord of the Rings’ is used as a reference point, the 12 volumes can be roughly separated into 3 parts:

Before ‘The Lord of the Rings’, which comprises volumes 1-5; during the writing of ‘The Lord of the Rings’, from volumes 6-9; and after the story was completed, volumes 10-12.

Notes on ‘The Hobbit’ aren’t included in the ‘History’.

This won’t be presented the way I usually write reviews, instead I’ll give a brief description of each volume, followed by my overall impression at the end.

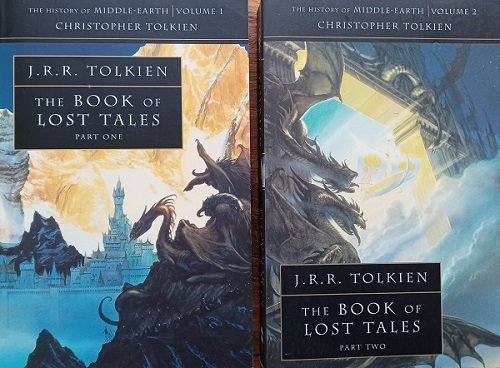

Cover art by John Howe - ‘The Fall of Gondolin’ (L) + ‘The Doors of Night’ (R)

The first 2 volumes are ‘The Book of Lost Tales Part 1’ and ‘The Book of Lost Tales Part 2’.

These books contain some of JRR Tolkien’s earliest writings, written around the years of the First World War, from 1915 to the 1920s.

He started writing them when he was about 23, and they’re the first versions of the tales that would evolve to become the stories in ‘The Silmarillion’.

If you’ve read ‘The Silmarillion’, you’ll recognise familiar elements even though they’re either named or framed differently.

Volume 1, ‘The Book of Lost Tales Part 1’ includes the stories set in the Blessed Realm and is told from the perspective of a mortal Man who visits the Isle of Tol Eressëa, where the Elves live.

Our first introduction to this Man names him as Eriol from somewhere in northern Europe, but, in later versions, his name is changed to Ælfwine, which means ‘Elf-friend’ and he’s an Englishman from the Middle Ages.

Instead of the Elven tales simply being narrated to Eriol/Ælfwine, Tolkien has chosen to frame the Man’s arrival and meeting of the Elves in a narrative titled ‘The Cottage of Lost Play’.

While some might find the incidents relating to the Cottage and its inhabitants a tad ‘twee’, maybe a little too like a child’s fairy tale, I liked the imagery conjured and the thought process behind it.

Tolkien’s poetical phrasing is already in evidence, as can be seen here where he describes how Yavanna, one of the Queens of the Valar, sang the awakening of all growing things in the world:

‘Alone in that agelong gloaming she sang songs of the utmost enchantment, and of such deep magic were they that they floated about the rocky places and their echoes lingered for years of time in hill and empty plain, and all the good magics of all later days are whispers of memories of her echoing song.’

Volume 2, ‘The Book of Lost Tales Part 2’, contains first versions of the tale of Beren and Lúthien, the Túrin saga, and the full narrative of the Fall of Gondolin, which, among other details, lists the 12 Houses of the Elves of Gondolin, the people of Turgon.

‘The Nauglafring’, which is the tale of the Necklace of the Dwarves (later renamed ‘Nauglamir’), is described as ‘lost’ (in that it was never fully rewritten) and much of it is excluded from ‘The Silmarillion’.

The book also has the only full narrative of Eärendil’s travels.

Obviously, all these tales are still in rough forms.

These 2 books also contain a short list of obsolete and archaic words, which I found an enjoyable addition, for example: ‘an’, which means ‘if’; ‘clamant’, meaning ‘clamorous, noisy’; and ‘wildered’, meaning ‘perplexed, bewildered’.

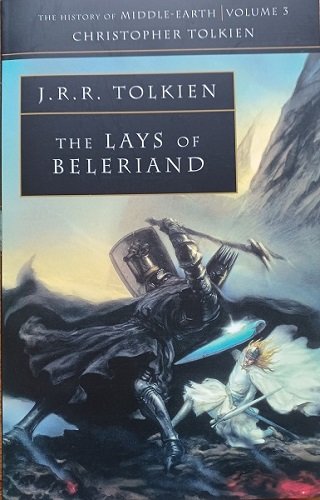

Cover art: ‘Fingolfin’s Challenge’ by John Howe (Fingolfin and Morgoth)

Volume 3 is ‘The Lays of Beleriand’ which contains 2 epic poems, the Legend of Túrin Turambar, and the story of Beren and Lúthien.

The poems are incomplete, much of them still in draft form, which is so unfortunate as what we do have is amazing.

Yes, we know how the stories end, but to see them in the form of epic poems adds an archaic layer on a par with Arthurian legends like ‘Sir Gawain and the Green Knight’.

Cover art: ‘The Siege of Angband’ by John Howe

Volume 4, ‘The Shaping of Middle-earth’, is basically the 1930s version of ‘The Silmarillion’, using the ‘The Book of Lost Tales Part 1’ and ‘Part 2’ as the basis, and significantly developing the stories.

This volume also includes a collection of maps, and the Annals of Valinor and Beleriand, which started off as chronological timelines before becoming full narratives.

Cover art: ‘The White Tower of Elwing’ by John Howe

Volume 5, ‘The Lost Road and Other Writings’, includes the first version of the legend of Númenor that was set apart from Middle-earth but was eventually absorbed into Middle-earth’s legendarium.

There are also subsequent drafts of ‘The Silmarillion’ stories, and ‘The Etymologies’, the best source on Elvish languages.

Then there’s ‘The Lost Road’, a fascinating story of the voyage of Ælfwine and his trip to Tol Eressëa that connects the legendarium tales to the present time as it also includes similar journeys made by other characters in later times.

This was Tolkien’s attempt at a time travel story, which came about from a challenge made between him and his friend, C.S. Lewis, back in 1936.

Part of their ongoing encouragement of one another’s writing, they came up with a challenge in which one would write a story about space travel, and the other, a story to do with time travel.

They tossed a coin, and Lewis got space while Tolkien got time.

Lewis finished his story, which was published as ‘Out of the Silent Planet’, the first book in his Space Trilogy.

Although Tolkien never finished ‘The Lost Road’, the foundation of the plot, which was meant to lead to the fall of Atlantis, formed instead the basis for the Downfall of Númenor.

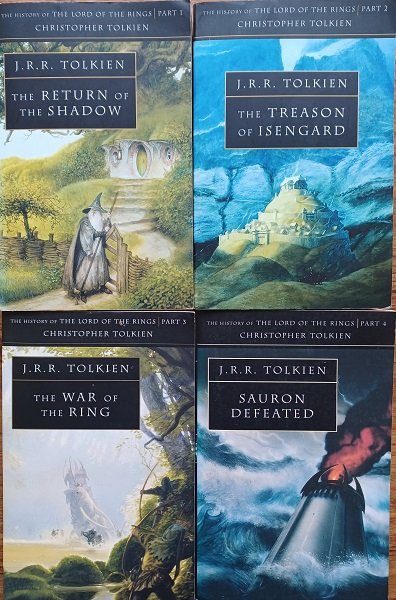

Cover art by John Howe - ‘Gandalf Returns to Bag End’ (Pt.1); ‘Edoras’ (Pt.2); ‘The Mûmak of Harad’ (Pt.3); ‘The Drowning of Anadûnê’ (Pt.4)

The next 4 volumes are to do with the period when Tolkien was writing ‘The Lord of the Rings’; basically, his first and subsequent drafts, which, being familiar with the story, and especially as a writer, I found tremendously fascinating.

Volume 6, ‘The Return of the Shadow’, covers the story from the start to The Mines of Moria, as described in the opening inscription:

‘… herein the journey of the Hobbit who bore the Great Ring, at first named Bilbo but afterwards Frodo, is followed from Hobbiton in the Shire through the Old Forest to Weathertop and Rivendell, and ends in this volume before the Tomb of Balin, the Dwarf-lord of Moria.’

Although Tolkien had originally written the character of the ranger, Strider, as a hobbit named Trotter, the early drafts already contain the characteristics of the man, Strider.

Volume 7, ‘The Treason of Isengard’; here ‘… the story of the Fellowship of the Ring is traced from Rivendell through Moria and the Land of Lothlórien to the time of its ending… beside Anduin the Great river, then is told of the return of Gandalf Mithrandir, of the meeting of the hobbits with Fangorn and of the war upon the Riders of Rohan by the traitor Saruman.’

Here is found the first entry of Galadriel and the initial ideas of the history of Gondor.

Galadriel’s gifts to Boromir, Merry and Pippin, and Legolas ‘are described in the same words as in [‘Fellowship of the Ring’]’

There’s also the original meeting of Aragorn and Éowyn, very different to what it eventually becomes.

Also included are the original map and an appendix examining the Runic alphabets.

Volume 8, ‘The War of the Ring’, traces ‘the story of the history of Helm’s Deep and the drowning of Isengard by the Ents… the journey of Frodo with Samwise and Gollum to the Black Gate, of the meeting with Faramir and the stairs of Cirith Ungol, of the Battle of the Pelennor Fields and of the coming of Aragorn in the fleet of Umbar.’

Regarding the introduction of Faramir, Tolkien had this to say in a letter he’d written to Christopher Tolkien in 1944 (letter 66):

“A new character has come on the scene (I am sure I did not invent him, I did not even want him, though I like him, but there he came walking into the woods of Ithilien): Faramir, the brother of Boromir…”

Volume 9, ‘Sauron Defeated’, contains ‘the story of the destruction of the One Ring and the Downfall of Sauron at the End of the Third Age.’

It also includes the ‘Notion Club Papers’, which could be considered a subsequent version of the Númenor legend, written as a time travel story with a science fiction flavour.

The story is structured around the minutes of meetings, written in the 1940s, of an Oxford club, no doubt inspired by the Inklings.

While writing this story, which include events that take place in the future, Tolkien mentions a great storm occurring in England in 1987, which, for him, was simply something he made up.

Yet, he’d unwittingly made an uncanny prediction because, in real life, the Great Storm of 1987 did, indeed, occur in October of that year.

This volume also includes the ‘Epilogue’ Tolkien had written to end ‘The Lord of the Rings’ that he ‘was persuaded by others to omit…’, a decision he ‘seems both to have accepted and… regretted…’

It continues from Sam’s words, ‘“Well, I’m back,” he said’, and is a lovely scene of Sam with his children.

The writings in volume 9 take us to about 1949, give or take a few years.

With the publication of ‘The Lord of the Rings’, Tolkien finally felt free to return to ‘The Silmarillion’ stories.

Cover art:‘The Killing of the Trees’ by John Howe (Morgoth and Ungoliant)

Volume 10, ‘Morgoth’s Ring’, takes us back to the writings, which began in ‘The Book of Lost Tales Part 1’, here revisited, post-‘The Lord of the Rings’.

One of the essays in this volume is ‘Laws and Customs among the Eldar’, which includes the naming customs of the Elves, and Tolkien’s conceptions of the soul and body.

Another interesting essay is one which deals with the situation when a married Elf dies but chooses not to be reborn and the consequences for the spouse who still lives, namely the situation with Finwë and Míriel, Fëanor’s parents.

My favourite essay is ‘Athrabeth Finrod ah Andreth’, a philosophical discussion between Finrod (Galadriel’s brother) and a mortal woman, Andreth, a wise woman, about the differences between Elves and the Edain (Men from the 3 Houses of Men) .

Their discussion has personal meaning for Andreth, who is of the Edain, for she loves Finrod’s brother, Aegnor, who, despite his acknowledged love for the mortal woman, left after a brief time of happiness.

Cover art: ‘Niënor and Glaurung’ by John Howe

Volume 11, ‘The War of the Jewels’ explores more of ‘The Silmarillion’ drafts, written in 1951.

Tolkien spent a lot of time reworking the stories in volumes 10 and 11; as he said in one of his letters (letter 19), “… the Silmarils are in my heart…”, and he wanted to produce as perfect a publishable version of ‘The Silmarillion’ as he imagined it to be.

Writing ‘The Lord of the Rings’ brought together much of the legendarium, and this probably made it easier for Tolkien to get deeper into the nitty-gritty of stories he’d begun way back before 1920.

I think that may well have given him the chance to devote more thought into expanding them instead of simply rewriting them.

Cover art: ‘The Ship of the Dark’ by John Howe

Volume 12, ‘The Peoples of Middle-earth’, has extra material on all the various appendices in ‘The Lord of the Rings’ from ‘The Prologue’ to the Languages to the ‘Akallabeth’ to ‘The Heirs of Elendil’.

‘Of Dwarves and Men’ details both races’ relationship to one another, and much of this information is not found anywhere else.

‘The Shibboleth of Fëanor’ has fascinating information to do, especially, with Finwë’s children and grandchildren, who included Fingon, Turgon, Finrod, and Galadriel.

There’s also a section with more information on Glorfindel and Círdan.

Also included is the sequel Tolkien attempted to ‘The Lord of the Rings’, set during the reign of Aragorn’s son, Eldarion, titled ‘A New Shadow’, but he aborted it after only about 13 pages.

There is a 13th volume, ‘The History of Middle-earth: Index’, which I haven’t got.

Compiled by Helen Armstrong, it’s basically the ultimate index, and includes the indices of all 12 volumes.

I can see the appeal as it would make it much easier to find a specific entry instead of diving into various books, trying to remember where a certain something is.

Overall thoughts:

I enjoyed reading all 12 volumes, and, while the ‘History’ can be heavy going in places, it’s possible to simply dip into them without having to read any particular volume cover-to-cover.

And, obviously, there’s lots of repetition over some of the volumes, especially once ‘The Silmarillion’ has, near enough, reached the form we’re familiar with.

Personally, I would not recommend ‘The History of Middle-earth’ for the casual fan.

This is for the Tolkien fan who truly wants to learn as much as they possibly can of Tolkien’s legendarium.

We get to go through Tolkien’s evolving drafts and recognise concepts that were already, more or less, ‘fully formed’, and that changed little for the final work.

For Middle-earth fans who have and love Tolkien’s well-known works that revolve around his extensively researched legendarium, I’d say it’s a must-have.

The great thing is you don’t need to get all 12 volumes.

If you’re only interested in Tolkien’s writings for ‘The Lord of the Rings’, then just get volumes 6-9.

My personal favourites, though, are volumes 10-12, chock-full of fascinating information.

Apart from ‘The Silmarillion’ writings, there are interesting essays on matters that enhance the main stories, like the First Battle of Beleriand, and the wanderings of Húrin after Morgoth released him; also, there’s more information on some characters, like Fëanor’s wife, Nerdanel, and their 7 sons.

I’m glad I finally got around to, not only getting the 12 volumes, but reading them too.

Even though there will always be parts of Tolkien’s legendarium I want to know more of, all the volumes of ‘The History of Middle-earth’ have been very satisfying to read and I know I’ll be returning to them repeatedly.

Well, that turned out to be a much longer post than I was intending!

If you’ve read all the way through, I thank you very much and hope you found this review/overview helpful.