The Sunday Section: Art - Lady Elizabeth Butler

I’ve not had the privilege – yet – of seeing any of Lady Butler’s paintings in person. Remarkably, she did not come from a military family, yet she is known for her paintings of historical battle scenes.

Elizabeth Southerden Thompson was born in November 1846 in Lausanne, Switzerland. Her parents, Thomas James Thompson and Christiana Weller, a concert pianist, had been introduced to one another by Charles Dickens. They had a younger daughter, Alice, who would become a poet and essayist, better known as Alice Meynell. The girls were fortunate in that both parents willingly and carefully fostered their education, and literary and artistic talents. Elizabeth studied painting with a tutor before going to the South Kensington School of Art in 1866.

To begin with, Elizabeth focussed on religious subjects in her paintings. But, in 1870, while in Paris, she was influenced by the battle paintings of Jean Louis Ernest Meissonier and his student, Édouard Detaille, and made the fateful decision to switch to war paintings.

'1814, Campagne du France' ~ Jean Louis Ernest Meissonier

'Vive L'Empereur' ~ Édouard Detaille

In 1873, she earned her first submission to the Royal Academy with a battle scene from the Franco-Prussian War, titled ‘Missing’.

In May 1874, Elizabeth Thompson became an overnight success when her painting, ‘Calling the roll after an engagement, Crimea’, better known as ‘The Roll Call’, was exhibited at the Royal Academy. The crowds were so great that a policeman had to be stationed by the painting. Not only the public but the leading painters of the day voiced their admiration. At the Academy Banquet, Elizabeth’s painting was singled out for praise by the Prince of Wales and the Duke of Cambridge, who was Commander-in-Chief of the British Army. Crimean veterans confirmed the accuracy of the details Elizabeth had included in her painting. Florence Nightingale, bedridden at the time, requested that the painting be brought to her; she gave it her seal of approval. ‘The Roll Call’ would become one of a handful of the most successful Royal Academy paintings of the century.

'Calling the roll after an engagement, Crimea'

The industrialist who had commissioned the painting, Charles Galloway, was inundated with offers from those wishing to buy that painting, but he turned them all down, including the Prince of Wales. For the first time in the history of Academy paintings, the painting was taken to Buckingham Palace so Queen Victoria could view it. When she expressed a wish to buy it, Charles Galloway was unable to refuse. But he expressed one condition, and that was for Elizabeth to paint him another picture. Taking into account her new-found fame, she shrewdly raised the price from £126 to £1,126!

In 1875, Elizabeth exhibited ‘ The 28th Regiment at Quartre Bras’, depicting, two days before Waterloo, the encounter between the 28th Regiment and the French cavalry. As observed by Henry Blackburn in his Academy Notes, “The spectator is, as it were, in the very thick of the fight, with the dead, the wounded, and the fainting, on the ground around him.”

'The 28th Regiment at Quartre Bras'

The leading art critic, John Ruskin, whose opinion was capable of making or breaking an artist’s reputation, admitted in his Academy Notes, that, to begin with, he was heavily prejudiced against the painting:

“I never approached a picture with more iniquitous prejudice against it than I did Miss Thompson’s; partly because I have always said that no woman could paint; and, secondly, because I thought that what the public made such a fuss about must be good for nothing. But … no doubt about it … the first fine Pre-Raphaelite picture of battle we have had … profoundly interesting, and showing all manner of illustrative and realistic faculty … it remains only for me to make my tardy genuflexion, on the trampled corn, before this Pallas of Pall Mall.”

Elizabeth’s fame notwithstanding, her mother, Christiana, was reported to have been distressed that her daughter painted nothing but soldiers and battles.

It was in 1875 that Elizabeth met the man she would marry – Major William Butler, a 39-year-old Irishman, and an officer of the British Army. He had already served in Burma, Madras, Canada, the Ashanti campaign, and in Natal. By the time he married Elizabeth in June 1877, he was “an intuitive sympathiser with rebel nationalists all over the Empire”. (James Morris). Although influenced by her husband’s beliefs that the natives in colonial lands were not best served by colonial imperialism, Elizabeth’s paintings continued to portray the valour of the ordinary British soldier.

'Balaclava' (1876)

'Return from Inkerman' (1877)

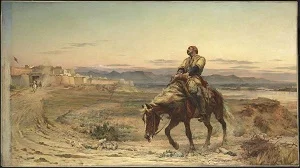

‘ The Remnants of an Army, Jellalabad, January 13th, 1842’ (usually called ‘Remnants of an Army’) was painted and exhibited in 1879. This, said to be one of her most evocative paintings, encapsulates the tragedy and endurance of the army.

'Remnants of an Army'

The painting depicts Dr. William Brydon, a surgeon of the Army Medical Corps, struggling towards the walls of Jalalabad. During the First Anglo-Afghan War, following an uprising in Kabul, Wazir Akhbar Khan agreed to allow the British army under Major General Sir William Elphinstone to withdraw to the British garrison at Jalalabad, over 90 miles away. Of the 16,000 people – the army, its dependants, and camp-followers – who began the journey, only Dr. Brydon and a handful of Indian sepoys survived. The rest had succumbed to exposure, frostbite, starvation, or were killed in attacks from Afghan tribesmen.

The 1880 painting, ‘Defence of Rorke’s Drift’, was commissioned by Queen Victoria, and inspired by the accounts of survivors.

'Defence of Rorke's Drift'

What is considered Lady Butler’s finest painting, ‘Scotland forever!’ was completed in 1881. It shows the Scots Greys at the Battle of Waterloo, charging, it seems, straight out of the canvas. One can almost hear and feel the thundering hooves of the galloping horses, as Lady Butler herself did:

“I twice saw a charge of the Greys before painting ‘Scotland forever!’ and I stood in front to see them coming on. One cannot, of course, stop too long to see them close.”

'Scotland Forever!'

Lady Butler accompanied Major Butler wherever his military career took him, including Egypt and South Africa. The couple had 6 children.

'Floreat Etona!'

The title of this 1898 painting, ‘ Floreat Etona!’ is the motto of Eton College, ‘ may Eton flourish’, and shows an incident during the Battle of Laing’s Nek (28 Jan 1881) in the First Boer War. It depicts two British officers in blue jackets, leading red-coated infantry in a frontal assault on a formidable Boer defence. The officer on the left of the painting, Lt. Robert Elwes of the Grenadier Guards, is shouting encouragement to another Eton old boy, adjutant of the 58th Regiment of Foot whose horse is stumbling. According to eye-witnesses, Lt. Elwes shouted, “Come along Monck! Floreat Etona! We must be in the front rank!” Elwes was shot and killed almost immediately, one of 83 killed and 11 wounded; Monck survived. This attack was the last time a British battalion carried its colours into action; a Queen’s Colour is visible in the background of the painting.

When Major Butler retired from the army, the family moved to Ireland in 1905, to Bansha Castle in County Tipperary. After Major Butler died in 1910, Elizabeth continued to live at Bansha. In 1922, she moved to Gormanston Castle in County Meath, the home of her youngest child, Eileen, Viscountess Gormanston.

'In the Retreat from Mons: the Royal Horse Guards' (1927)

Between 1873 and 1920, Lady Elizabeth Butler exhibited 24 paintings at the Royal Academy. She died at Gormanston in October 1933, shortly before her 87th birthday. In an autobiography published in 1992, she wrote, “I never painted for the glory of war, but to portray its pathos and heroism”.