Mummies Revealed at the British Museum

On Thursday, we went up to London, to the British Museum, for another stupendous exhibition – ‘Ancient Lives, New Discoveries: Eight Mummies, Eight Stories’. I’d originally planned to go to this exhibition, which is on till the end of November, in October. But, gripped by a spontaneous moment, decided to go this month.

We had an early lunch at a lovely Italian restaurant down one of the roads opposite the museum – all their food is made fresh on the premises, and it was wonderfully yummy. And so affordable, which surprised me, considering we were in central London. Opposite the restaurant was a gent's clothing shop, 'Thomas Farthing', with a penny farthing outside ...

As we were climbing the steps to the museum, Liam spotted this incongruous sign ...

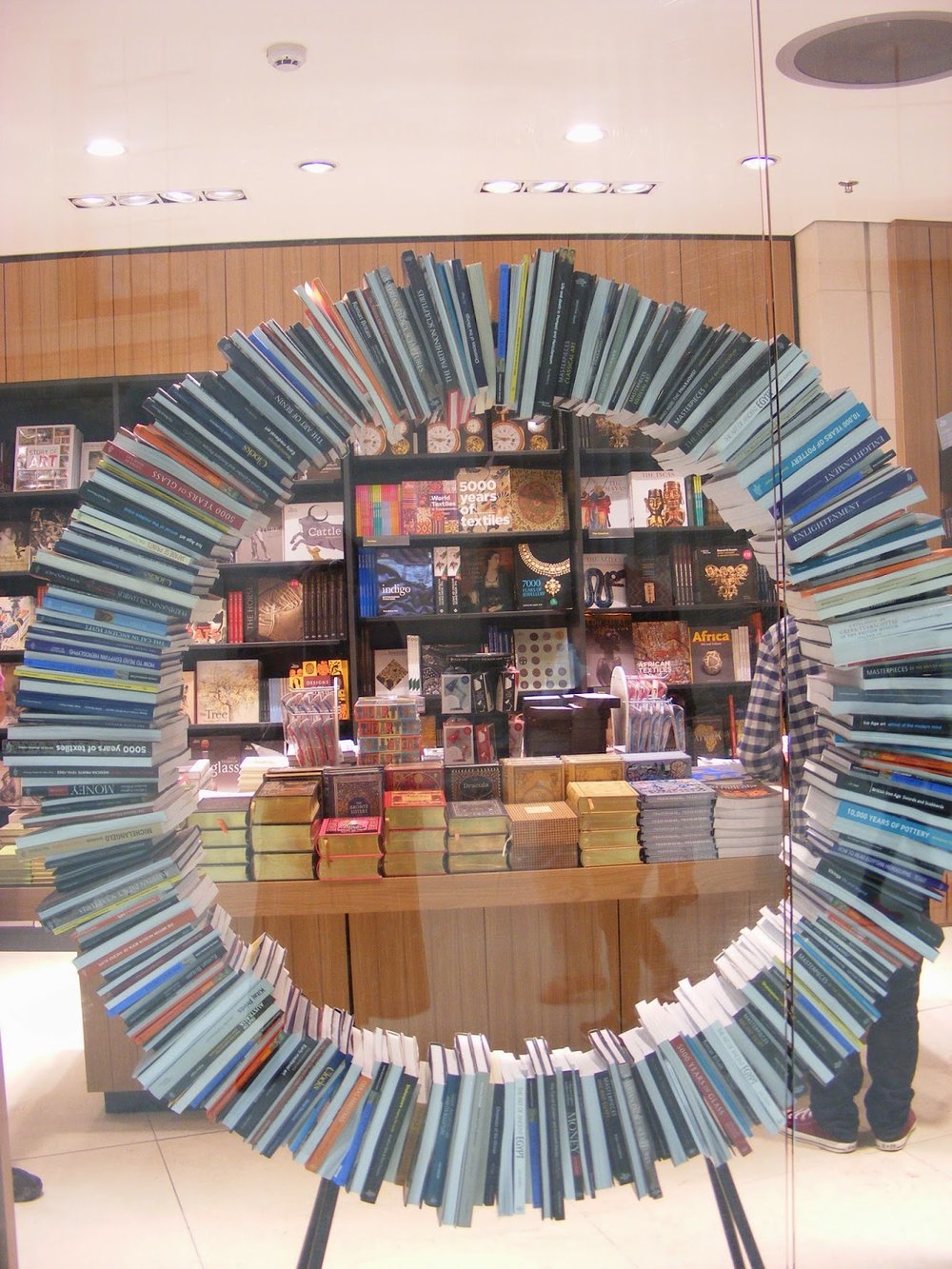

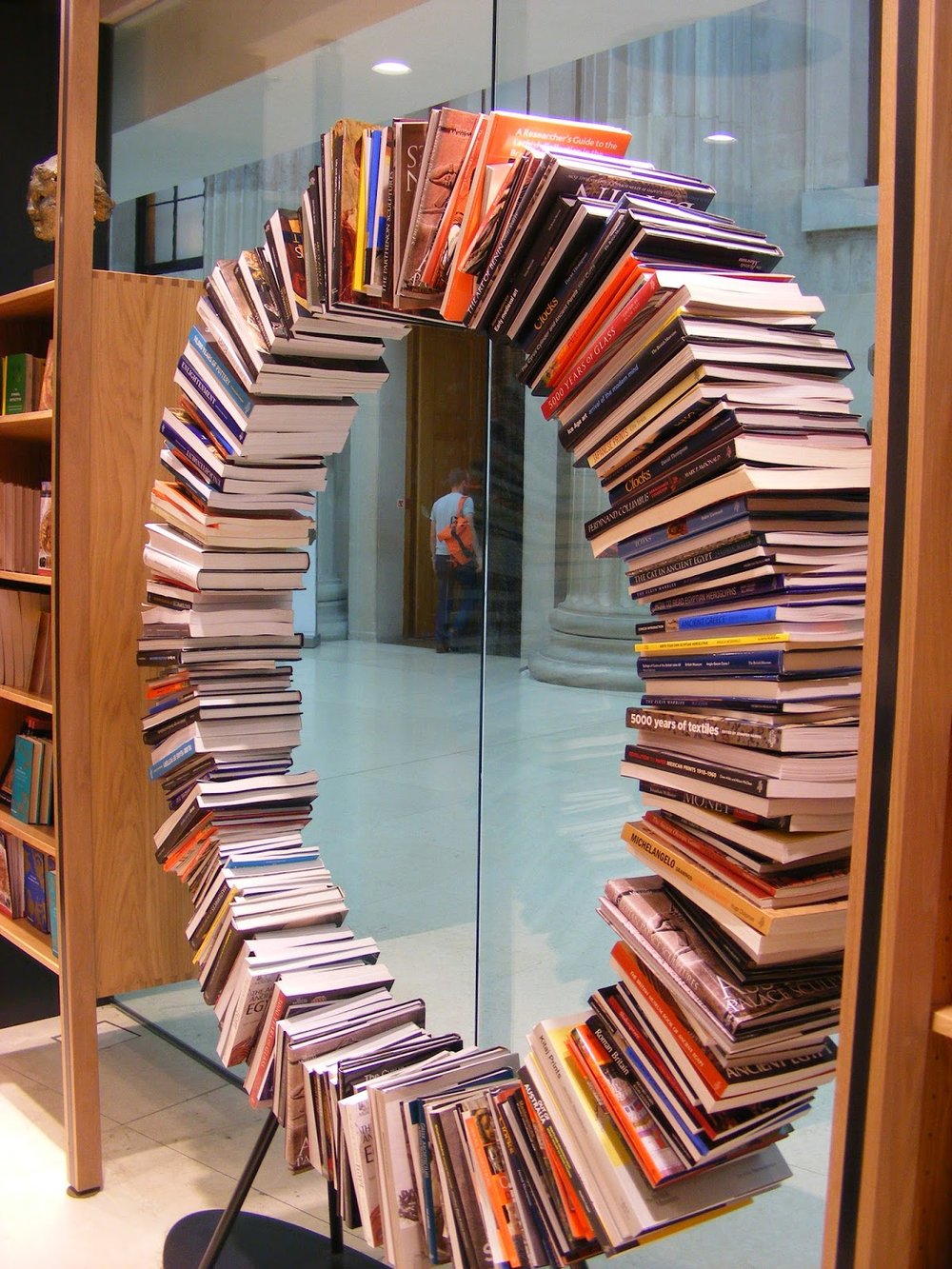

We had time to spare before heading in to the exhibition, so Gordon headed off to ‘Japan’, Liam to the Enlightenment Room, and I wallowed happily in the book shop, which had this fantastic display!

So, the exhibition ... it features 8 mummies from the museum’s own collection, which have been studied using the latest CT-scanning technology. “The mummies have been remarkably preserved … For each of the mummies featured, a personal profile is built up, leading to an investigation of a particular aspect of life or death in the ancient society to which they belonged. Diet, disease, personal adornment and childhood are just some of the themes covered.”

Not surprisingly, photography was not allowed. But, surprise, surprise, I treated myself to the book of the exhibition, by John H. Taylor and Daniel Antoine. I’ve included a mere handful of the pictures that are in the book to basically give those who don't get a chance to get to the exhibition a glimpse of how amazing it is.

Each stage of the virtual unwrapping was projected onto screens, large and small. Layers were peeled back to show the bandages, in some cases, the skin, skeleton, internal organs, brain residue, even partially digested food, and objects that had been placed in with the mummies. One of the mummies had part of the embalmer’s tool still in its skull, where it had broken off.

This was the first, a man about 20-35 years old, who was discovered at Gebelein in Upper Egypt, and is over 5,000 years old. It is truly mind-boggling, how well preserved he is; most of his skin, some of his hair and nails have survived. Even though he's been dead for so long, it was still ... sad, seeing him lying in the glass case.

Because he’d been buried in the hot, dry desert sand, his preservation was totally by natural processes. “The decay of a corpse is caused by the actions of enzymes, chemicals which are present within the body and which after death break down the fats, proteins and carbohydrates that make up the soft tissues. The process is advanced by bacteria from within the body and from the environment, and often by insect activity …” In this case, the “rapid drying by extreme heat” halted these processes, thus preventing decay.

CT scan showing preserved brain and lungs (highlighted in blue), and, probably, partially digested food in pelvic area

This man was aged over 35, and was found in Thebes; his mummy is over 2,500 years old.

This is the one that has part of the embalmer’s tool still in the skull. Ancient Egyptians believed that the heart was the centre of the body and the consciousness, and attributed very little importance to the brain. That was why the brain was removed and discarded before mummification. The embalmer would insert an iron hook up the nose to access the brain and remove it; what the hook could not reach would be rinsed out. Despite the small amount of space to work with – the nasal cavity – still the embalmers perfected their technique; most of the delicate nasal bones suffered little, if any, damage.

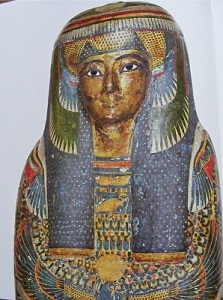

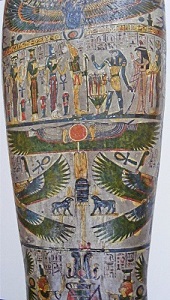

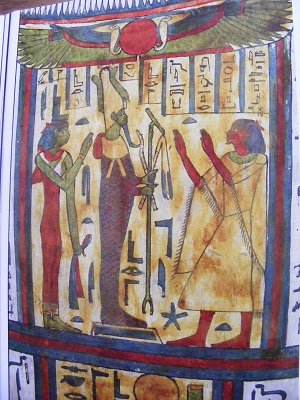

This female mummy, almost 3,000 years old and discovered at Thebes, was a priest’s daughter; her name was Tamut, a shortened version of a name that is spelled differently each time it appears on her cartonnage case. Cartonnage is a technique similar to papier-mache, and is like a full-body funerary mask. It’s made of layers of linen or papyrus, which is then covered with plaster.

Tamut’s internal organs - liver, lungs, stomach and intestines - were removed and desiccated, but were not placed in canopic jars; instead they were placed in her chest, each bundle containing an organ and a figurine of one of the Sons of Horus - Imsety (human); Hapy (baboon); Duamutef (jackal); and Qebehsemuef (falcon). CT scans also show that she was adorned with amulets – a winged goddess covers her throat; a falcon lies across her breast; a carved scarab beetle lies on her chest; a vulture has been carefully placed on the pubic area; and a winged scarab is on her feet.

This mummy (about 2,700 years old) of a temple doorkeeper, Padiamenet, was found in Thebes; he was about 35-50 years old.

Truly remarkable how, after thousands of years, the colours are still so vibrant.

He proved to be too tall for the cartonnage; the scans show that his feet protruded well out of the base. To cover them, layers of linen were wrapped over his feet and attached to the bottom of the cartonnage, but were left unpainted.

Although this mummy (about 2,800 years old) has the appearance of an adult woman, it is actually of a little girl, aged about seven, a temple singer named Tjayasetimu.

Her mummy case is unusual because it’s been fashioned to look like a living person with limbs free from the wrappings of the dead. Her mummy has been so carefully preserved – scans show clearly her eyelids, lips and nose, and even her hair.

This unknown man found in Thebes is from the Roman period, the 1st to 3rd centuries AD.

I found this one particularly unsettling and sort of creepy. His appearance is almost ‘fleshy’ – cloth was used to accentuate his chest and thighs. Limbs and digits have been individually wrapped, yet his hair and scalp have been left exposed; facial features have been painted on.

This, for me, was the most poignant mummy – a 2-year-old, found in Hawara (over 1,900 years old).

His cartonnage is so small, it would have been possible to cradle it in both arms without any difficulty. The highly decorated cartonnage shows that he was treated with care in death.

The last mummy (about 1,300 years old) is a Christian woman from Sudan, aged about 20-35 years, found wrapped in textile.

Amazingly, a tattoo is visible on her inner thigh, where the wrappings have disintegrated. It is a monogram of the Archangel Michael, who played a very important role in Christian Nubia.

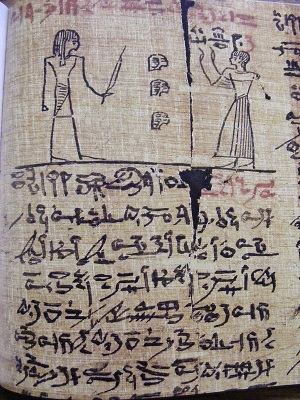

Section of a funerary papyrus, in hieratic, with spell 43 of the Book of the Dead - to protect the deceased against the danger of being decapitated in the afterlife.

It was a truly fascinating exhibition with just enough information to answer the obvious questions, without overloading you with too much.

We still had time after the exhibition … as Gordon had waxed lyrical about ‘Japan’, Liam and I decided to go give it a look-see, while Gordon headed off to the book shop. As the lift looks really ancient and flimsy, Liam said he’d rather take the stairs so off we went.

The top of the lift - first time I've seen it.

A netsuke of a seahorse

Another netsuke - badger in monk's robes - adorable!

Netsuke of lizard on skull

This stunning piece - 'Large Feather Leaves Bowl' - is by Hosono Hitomi. She made the mould for the leaves from a tree outside her studio in Ladbroke Grove. From that one mould, she created 1,000 leaves ... yet she has managed to individualise each one! She attached each leaf by hand, 'using chopsticks to fasten them inside the interior of the vessel first and then building them upwards and outwards. Each leaf is worked in such a way that it appears to be rustling in the wind.' Even though I know it's made of porcelain, still I half-expected to hear those leaves rustling.

'Long Landscape' handscroll; this is a copy but the original artist, Kano Osanobu, painted this when he was aged 14!

The next lot of pictures were taken in the samurai section ...

Traditionally, samurais used saddles made of wood. This type of saddle was first made in the Heian period (794-1185) and was used right up to the 1800s. The shape provided support for the archer or swordsman to fight while on horseback.

Saddle decorated in lacquer and shell inlay ...

... with dragons, clouds, and diamond patterns

Stirrups! Made of iron, they would have given the archer or swordsman a firm platform on which to stand and fight while on horseback

Helmet, reminiscent of a sea creature

Travelling case for sword

A companion sword - a 'wakizashi' - was worn at all times, indoors and out, by samurais.

Blade for a 'wakizashi', and a 'wakizashi' mounting. The various components are 'tsuba' (sword guard), hilt, scabbard, 'seppa' (spacers), 'kokatana' (utility knife), 'kogai' (pointed metal tool that splits to form chopsticks), and 'habaki' (collar to ensure a tight fit of the sword into its scabbard)

'Tanto', short sword, or dagger, and scabbard. Samurai women learned how to use daggers. In extreme situations, they were expected to fight, or stab themselves rather than be captured.

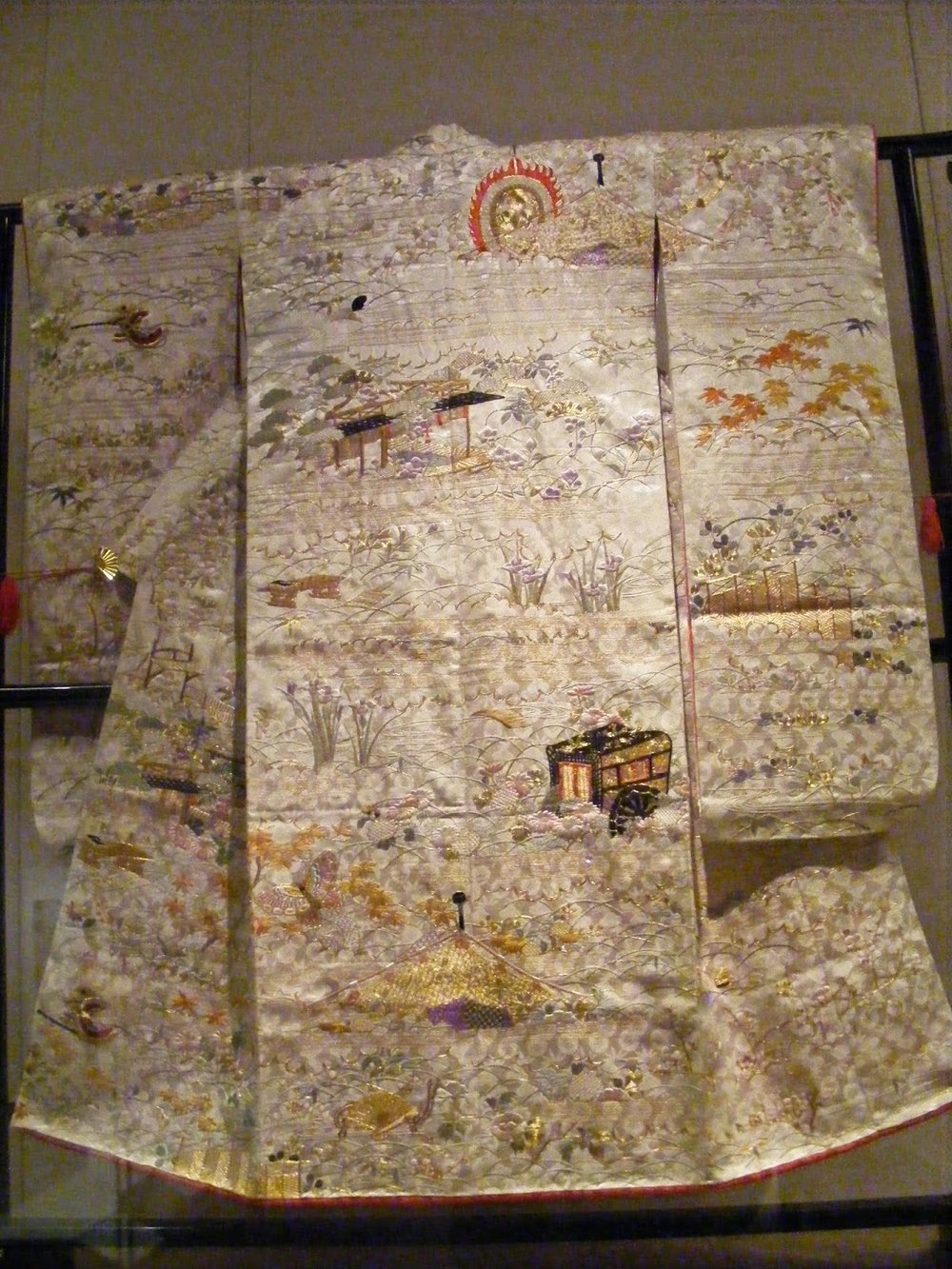

Bridal outer gown, worn over kimono and sash

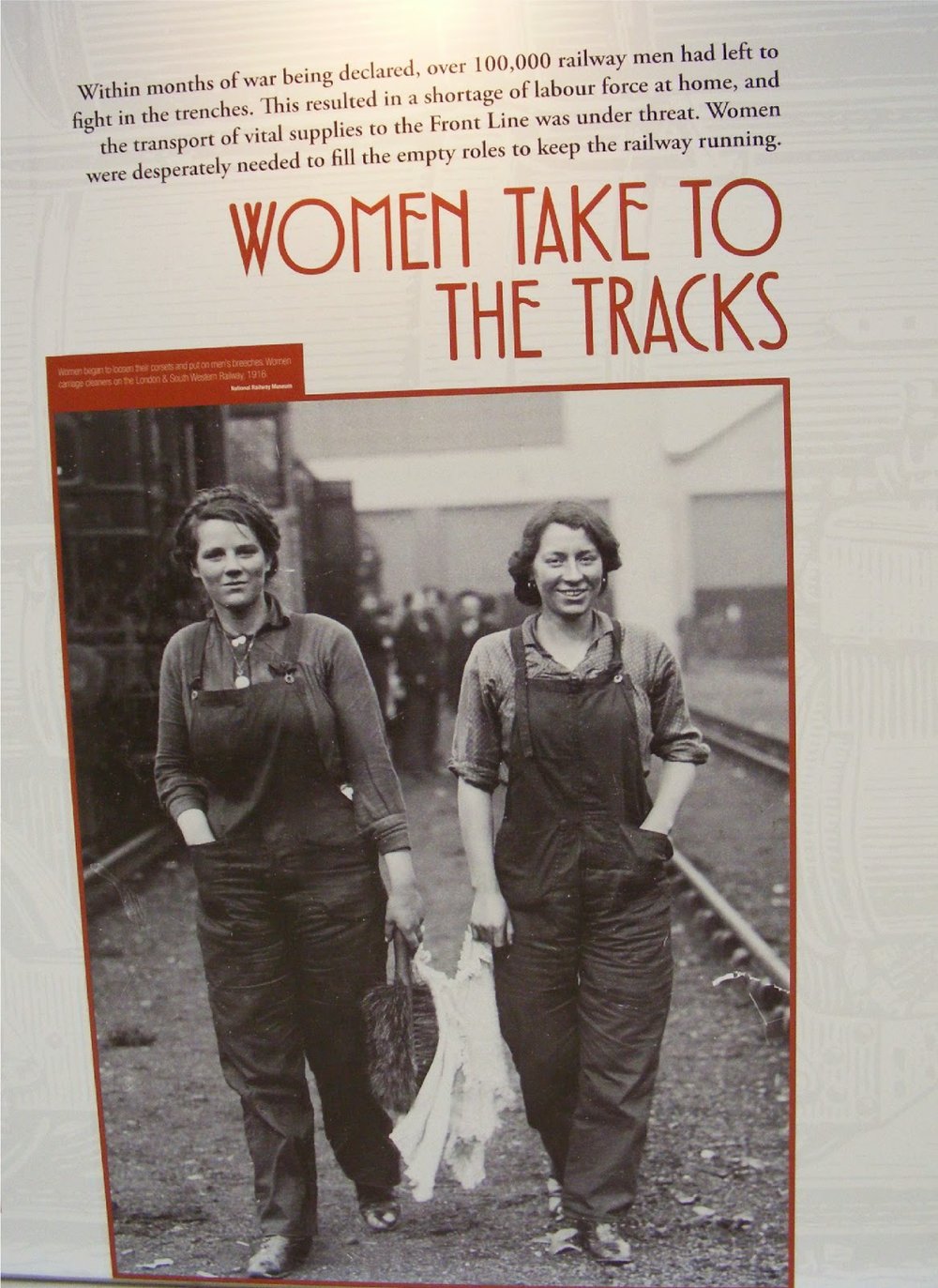

Took these at Waterloo station ...

All in all, it was a lovely day out – probably because it was the beginning of the school year, but the museum was delightfully uncrowded, and even our train journey home was good.